Archive for the ‘law’ Category

End of radio silence!

Another long gap between posts…

I have been writing and editing and re-editing my book on street art, law and the city, and, as I have mentioned before, whenever I am immersed in academic writing I find it hard to switch my brain into blogging mode.

I’ve also done a year’s teaching, compressed into the months between April and August.

And I’ve been travelling: I spent 3 months in London (with trips to Paris and Istanbul), and have been back to Berlin recently, and am currently in London. Much of this has involved fieldwork for further research – this time on the uptake of street art in cultural institutions, the art market, architecture, and so on. More on those issues later.

I’ll post some photos from recent trips soon.

In the meantime, here’s a link to my upcoming book, Street Art, Public City: Law, crime and the Urban Imagination.

http://www.taylorandfrancis.com/books/details/9780415538695/

The publisher, Routledge, like many academic publishers, is bringing out a hardback edition first, with a paperback to follow (in about 8 months). This is kind of frustrating for me, because hardbacks are expensive. So when you click on the link below you will see that the book is pretty pricey. If you feel inspired to order it, you can reduce this hefty price a little by entering the discount pre-order code LAW202013 at the checkout.

I’m excited to see it finally in print; if you read it, I hope you find it interesting.

Occupy Wall Street – an essay in images

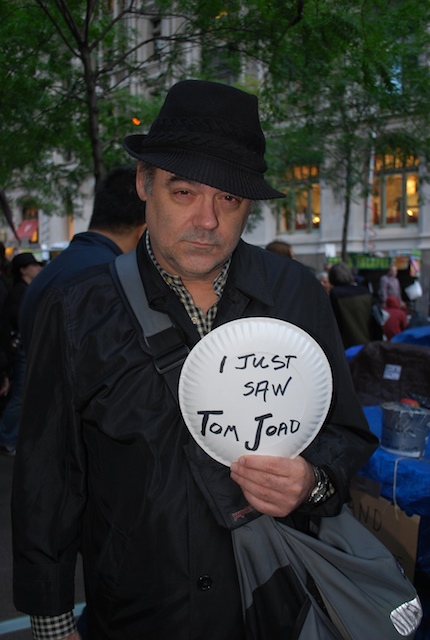

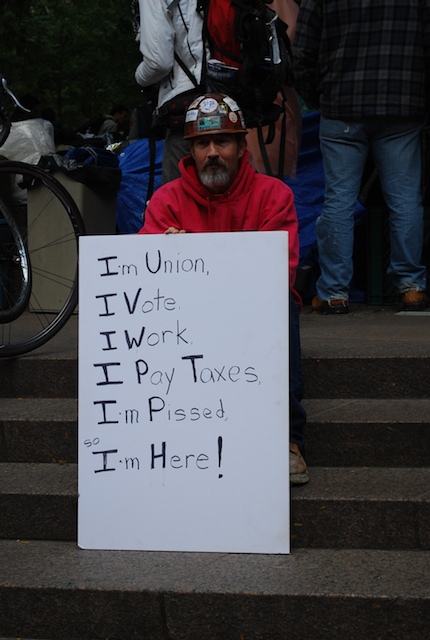

I’m in New York for a conference on law and the image, so this afternoon I went to see the Occupy Wall Street protest that has been happening there for a number of weeks now. As most people will know, Occupy Wall Street actually occupies Zuccotti Park, which is close to Wall Street, and is a conglomeration of disparate protests, protesters, issues and aims, loosely united under the banner slogan ‘We are the 99%’. Many of the issues being raised and protested there are to do with corporate greed, fraud, exploitation, and so on, but many are also protesting about issues such as campaign financing, the dispossession of native Americans, the stop and frisk laws that allow police officers to search individuals based on stereotyping rather than on evidence-based grounds, and many more.

Many others have written about Occupy Wall Street, and the various related protests occurring around the globe, including in Melbourne. For a sample, check out an excellent essay by McKenzie Wark; today’s Guardian article about the arrest of Naomi Klein at a related protest; and the We Are The 99% tumblr site.

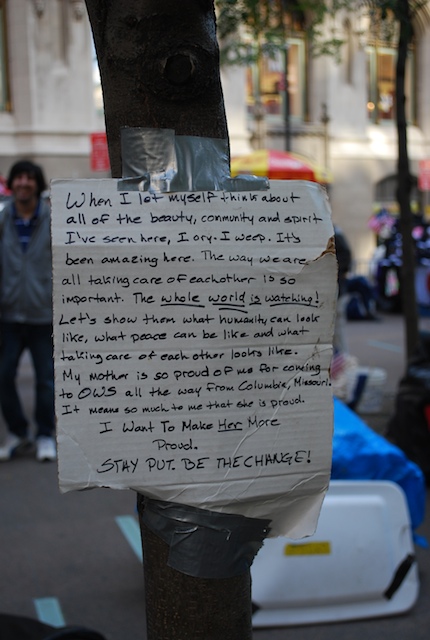

Instead of adding a lot more words to what has already been written, I thought I would put together some of the photos that I took today, to try to convey a sense of the protest and the place it is taking place in. To situate it, you have to imagine a small city park, no grass, just concrete, with some floral beds and a lot of trees. The park constitutes a small open space in the midst of some of New York’s most corporate and most solid skyscrapers. (To add a further, uncanny, dimension to the protest’s location, the park is diagonally across an intersection from the World Trade Center site, where the 9/11 memorial is, and where new skyscrapers to replace the lost Twin Towers are being busily constructed.)

This little park is filled with people: protesters, journalists, photographers, tourists, visitors. Around the park’s perimeter, police officers lean against barriers, monitoring the protest, and stepping up at frequent intervals to instruct people taking photographs or speaking with protesters to ‘move along’ and ‘clear the sidewalk’ (no doubt this is part of the claimed right to control the sidewalk that Naomi Klein adverts to in her account of her arrest).

Here, then, is a glimpse into Occupy Wall Street, as it took place on the afternoon of 20 October 2001.

What will happen at Zuccotti Park? How long will the protest last? No-one knows the answer to these questions, and they are probably the wrong ones to ask. What’s more important is that the protest is happening now, and that fact, each and every day that it is there, creates a politics in public space and demands a response. The lines of police outside the park, the rows of police vehicles in the streets, and the well-documented behaviour of the ‘white-shirted’ officers in their arrests indicate that the repression of the protest will be brought about some day (perhaps assisted by the weather, as the seasons shift from summer into autumn and winter). But even if that happens, Occupy Wall Street will have shown itself to be a formidable political peformance.

Space Invaders: The National Gallery of Australia’s exhibition of street art

It’s never unproblematic when galleries and museums exhibit the work of street artists – some believe that street art is no longer ‘street art’ when it’s exhibited indoors in a gallery or museum space; others think that whatever constitutes the ‘street’ aspect of street art is more of a free-floating sensibility that pervades certain artworks whether they are installed inside or outside; still others believe that genuine ‘street art’ must be carried out illegally in public space and anything that doesn’t meet these criteria is rather a kind of site-specific artwork or is graphic design work or is even a form of advertising. These issues have been debated and argued over in many different fora (and the book that Miso, Ghostpatrol, Timba and I recently published, Street/Studio, is partly about the tensions – productive as well as constraining – that arise when artworks move between street and gallery).

Whatever your opinion of the street/studio relation and its implication for street art, there is, however, no denying the importance of a major cultural institution putting on a large-scale exhibition of street artwork – and such an exhibition is about to open at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Its exhibition, Space Invaders, opens on 30 October (and runs until 27 February 2011, touring in 2011 to other cities). You can read here about the scope of the exhibition, which covers street art’s links to graffiti, its diversity of forms (including stickers, stencils, paste-ups, and so on), its connections to zine culture, the impact of pop culture upon the look of Australian street art, and its recent expansion into labour-intensive media involving drawn images.

I’m going to Canberra this weekend (along with a stellar bunch of some of Australia’s greatest street artists) for the opening festivities, and will be able to report next week on how the exhibition looks…. But it seems impossible to ignore the significance of this particular moment: Australia’s national gallery is putting on an exhibition dedicated to an art form which is often the product of activities deemed illegal by state governments and local councils in Australia, and many of the artists celebrated in the exhibition routinely risk fines or other punishments in order to make the artworks featured in the exhibition. Do we just chalk this up as being yet another instance when municipal and local governments are out of step with wider culture? Or is it time for local and state governments finally to admit that their persecution and prosecution of street artists and graffiti writers is just plain wrong?

Update on the Graffiti Prevention Act…

Back in 2008, I posted an entry about the newly introduced Graffiti Prevention Act here in Victoria… The State Government created that Act as part of its ‘get-tough’ stance on graffiti: the Act expands the definition of graffiti (so that more activities are now classified as graffiti), gives the police greater powers in responding to individuals they suspected of writing graffiti (increased powers of search and seizure, for example), and gives powers to councils to enter properties in order to remove graffiti without requiring the property owner’s consent (previously that was impossible).

It also created a raft of new and harsher penalties for those convicted under its provisions, and was constructed so that individuals facing a charge under the Act would be likely to pay an on-the-spot fine rather than try to contest a charge through the system (and in ensuring that on-the-spot fines were the preferable option for individuals facing a charge you could almost say that the Act engages in a bit of revenue-raising, like parking fines, for the State).

Contesting charges was made harder by virtue of the Act reversing the burden of proof so that anyone suspected of being a graffiti writer has to convince the police officer that they are carrying, say, an aerosol can for legitimate purposes rather than for writing graffiti. (Previously, and in relation to most offences rather than ones involving the possession of drugs, police officers had to actually do some detective work and ensure that they have evidence proving that the person charged had committed the offence.)

Back in 2008, I commented that it was likely that the Act would increase the number of individuals being criminalised by the system, and, since it facilitated police reliance on stereotyping in relation to who might be a graffiti writer, would have a disproportionate effect on young people. At the time I was writing, police officers were being trained in the implementation of the Act, and there was no information about how they were going to put it into operation. But now, thanks to an article in The Age newspaper recently, we can finally get a sense of what the police are doing with their new powers.

And the news is not good: what they are doing is more or less as I predicted, at least according to the article, ‘Graffiti tags help police put names to offenders’, by Andra Jackson in The Age on 22 December. The article describes a police operation, apparently in one municipality of Melbourne (Kingston) rather than city-wide or statewide, in which police have ‘raided the homes of 53 teenage suspects’ over the last year. The Act gives police the power to apply to a magistrate for a search warrant ‘when they have reasonable grounds to suspect’ that the individual has been writing graffiti. In the resulting raids, police have taken possession of aerosol cans, sketchbooks in which tags are practiced, and any other item which has been tagged.

In the article, the author states that the police ‘acted on intelligence’ to carry out the raid. I presume this means they obtained sufficient information to go before a magistrate and get a search warrant. It’s not clear how much information a magistrate would require before granting a warrant but if one year results in 53 warrants being granted in this one municipaility, I’m thinking that the local magistrates aren’t being overly strict with their interpretation of the Act).

The article doesn’t go into details of what actually happened to these 53 teenagers, but simply says that ‘usually’ they are given a community-based order by the Childrens Court. (Subsequent offending under the same Act will result in being sent before the Magistrates Court where higher penalties will apply.) So it would appear that one of my speculations about this Act was pretty accurate: would these 53 individuals have been brought before a court prior to the inception of the Act? Maybe some, but I would doubt that all of them would have, and so the Graffiti Prevention Act is proving to be a clear instance of what in criminology is called ‘net-widening’, where people who would otherwise not have been at risk of acquiring a criminal record and facing punishment within the system are now included within its ambit.

In terms of my other prediction – that the Act would facilitate the steroetyped targeting of young people – well, that seems to be coming true as well. This particular police operation was directed at two groups of people: the first involves teenagers, as already mentioned (because no-one other than teenagers ever does graffiti, right??), and the other is retailers who sell spray paint to teenagers. This other part of the police operation even involved sending under-18 year olds posing as would-be graffers into shops to attempt to buy aerosol paint during one week in December. Any retailer who sold paint to the kids was arrested. According to the article, 24 shops were approached, and ‘half willingly sold the students paint cans and other tools’. Throughout the last year, 120 retailers were charged with 1310 offences of this type. The penalty is an on-the-spot fine of $234 (hello!), and any subsequent offence sees the retailer in the Magistrates Court facing a $2000 fine. But even though this second group involves retailers, what’s striking is that the concern is with retailers who sell paint ‘and other tools’ to under-18 year olds, meaning that this issue has acquired its currency only because it relates to graffiti by young people. And it’s in this way that the Act is proving to be a powerful and flexible tool in the criminalisation of young people and others associated with their (illicit) activities.

It’s interesting that there’s been so little information until now about how the Act has been used since its implementation. I would very much like to know what is being done by the police in other parts of Melbourne and Victoria. It’s possible that perhaps the Act isn’t being used to criminalise more and more young people – but, I have to say, I doubt it. The State Government created the Act for exactly these purposes (against the advice of many individuals and groups), and it looks, sadly, as though the Act is doing what it was made for.

Three Variations on a Theme of Surveillance

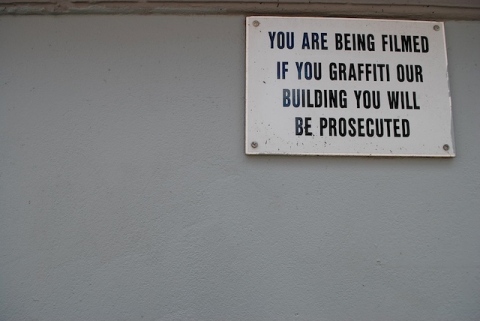

So much street art and graffiti depends upon thwarting the technologies of surveillance. I was looking back through some photographs taken on a trip to London last July, and came across three images, each of which are to do with surveillance in different ways.

Here’s one, taken in Rivington Street:

I like the double-layering that my photograph creates. The notice announces the fact of being filmed, at the same time as my camera films the notice.

This type of notice and device is typical of what can be seen all over London (and in many other cities around the world). London has filled itself with surveillance mechanisms, the most obvious of which is of course the closed circuit TV camera. They can be seen in so many streets, angling downwards from their elevated positions, like ugly metallic carbuncles on the walls of buildings. And the idea is certainly that in the streets where a camera can be seen, you can be seen on camera (although this Big Brother-esque cliché is often not true in practice: a few years ago I visited the control room for Melbourne City Council’s many CCTV cameras, and staff there admitted that there were so many screens and so few staff that it was impossible for them to properly see much of what was filmed).

The camera on the wall is just one type of surveillance device; there are others. One is the Oyster travel card that allows users to move between modes of public transport. As they travel, it deducts the cost of their journey from a prepaid account in their name. Super convenient, of course,, but when I was visiting there were a number of interesting stories in the media about how the Oyster system was being used to provide information about people’s day-to-day movements. Cases were cited of individuals who believe their spouse or partner is cheating on them looking at their Oyster statements to check where and when they travelled, in the hopes of revealing illicit trysts. Others believe that such computerized systems can be used for data profiling, either for more extensive marketing and advertising or for the straightforward surveillance of citizens that all governments engage in.

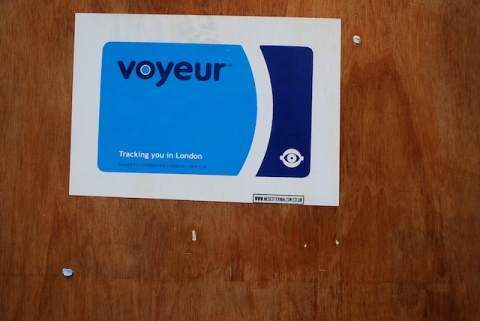

And one street artist in London was promulgating a critique of the surveillance systems surrounding citizens: Xylo’s stickers denouncing the Oyster system and mobile phone records were everywhere in 2008. Here’s one, in which he has transformed the very recognizable Oyster logo into the word ‘Voyeur’:

The final image doesn’t survey, and doesn’t denounce: instead, it transforms. The phrase ‘Bill stickers will be prosecuted’ is well known; it announces that bill posting or sticking is a crime and acts as a warning to anyone engaging in the activity. (It has also led to a commonly-seen variety of corny graffiti, in which individuals might write, as a riposte, ‘Poor old Bill Stickers’, or something similar.) In Brick Lane, I found this object affixed to a wall:

The artist has taken a printed version of the warning, and has edited it (illegibly now), and reconstituted it as part of an artwork itself. Thus the will to prosecute (to ‘put someone in the frame’, as the police might say) has been transformed into an image, itself framed and hung upon a wall, in public space, for all of us passers-by to see it, and to smile.

Art and the senses

I’ve been thinking for some time about the ways in which we experience an artwork, whether it’s located in the street or in a gallery. The most conventional way in which to think about this would emphasize vision – after all, we are used to the idea that an artwork is something that we look at.

But this leaves out other sensory dimensions, ones which are not so commonly talked about in relation to art. Is it possible to hear an artwork? Can we taste it?

In some works, image and sound are certainly inextricably combined, so that it’s not really possible to think in terms of simply looking at it or listening to it: Bill Viola’s work is a great example. Some artists entirely ignore the visual in favour of the auditory: in 2008, for example, an artwork called Speed of Sound Nau Interactive Bells was installed in Union Lane in Melbourne (this laneway was mentioned in a previous post, Street art and ‘authority’): the sound of bells, chiming at irregular intervals, played from speakers installed at different heights along the laneway walls, so that the sounds increased and receded according to one’s progress along the laneway.

And I’m also pleased to be able to report that I have had the experience of eating art. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a Cuban-American artist, created installation pieces in which lollies (or candies, or sweets, depending on which continent you live on) were strewn across a gallery floor or piled in its corners. Spectators were able to dip their hands into the artwork and pull out a handful of sweets to take home or to eat. You can get a sense of what Gonzalez-Torres’s wonderful work looks like if you click here – the tiny golden objects piled against the walls constitute one of his works, Untitled (Placebo – Landscape for Roni). I can still vividly recall how transgressive it felt, to pick up a piece of an artwork and put it in my mouth and taste it (it was lemon-flavoured, in case anyone is interested).

The spectator’s relationship to that particular artwork involved touch as well as taste: touching art is definitely something that is actively prohibited by most museums and galleries as illicit behaviour in relation to art: think of all those signs on the wall, saying ‘Do Not Touch’.

One of the most memorable instances in which I was able to touch an artwork certainly had a sense of the illicit about it. I was visiting a gallery overseas to chat with its director, and was informed by him that he had just received a shipment of works by one artist who would be featured in their next show. The director was hugely enthusiastic about this artist and invited me not just to look at the works but in fact to touch one. As I ran my fingertips over a tiny section of the work’s surface, I felt acutely aware of how forbidden such an act usually is.

In addition to the simple transgressive pleasure that came from touching a painting, I also felt a strong sense of how much my relation to the image was altered by the act of touching it: instead of standing facing it, as it would hang on a wall with me looking directly at it, it was brought towards me and held close to me, lying at an angle, slightly tilted from the horizontal, the light slanting off its surface, my gaze directed downwards, and my hand drawn towards it. Much later, I realized that part of the extraordinary charge that arose for me in this moment derived from the experience of relating, momentarily, to the artwork as if I was in the position of the artist. I don’t mean that I experienced a sense of acquiring any of the artist’s skills or abilities, but rather simply some of the privileges that come with the position of the work’s creator: the ability to touch it, the ability to stand close to it (rather than behind a white line in a museum), the ability to look at it from different angles.

(Of course, anyone who buys an artwork acquires the rights and power to do all these things too, but it’s interesting that it is the artist that was evoked by my altered position in relation to this work, not someone with sufficient financial resources to purchase it.)

What about smell? Does art have an aroma, an odour? Artists themselves are usually well acquainted with the olfactory dimensions of their work (from spray paint, oils, acetone, lacquer, glue, and many other substances) but it’s something that isn’t often discussed when we think about spectatorship. And yet those smells can have a powerful affective impact on the viewing of an artwork. When I went to see an exhibition by the wonderful Jose Parla at Elms Lesters Painting Rooms in London last October, many of the works on display were recently painted: as a result, the gallery rooms were filled with a perfume of oil and varnish, which made me, as a spectator, feel extremely conscious of the works as things which had been brought into being through the artist’s exertions with canvas, and paper, and paint.

It was on the same visit to London that I had the good fortune to meet the charming Nick Walker (you can see more about Nick here). As we finished our conversation about his work, in a small room at Black Rat Press, Nick indicated a neat pile of prints sitting on a trestle table, awaiting his signature before sale. He removed the protective cardboard from the pile, so that I could see the image below. But when the cardboard was lifted, an amazing smell drifted from the pile of prints: it was an intense, concentrated smell of paper, and it was strangely beautiful. I’ll never forget standing next to that table, under a low-hanging spotlight, gazing at these prints and inhaling their smell – a potent reminder that artworks are utterly material, not ethereal images floating free of the world of things.

Much of what I’ve been describing relates to the phenomenon of gallery or museum display, in which the smell or feel of an artwork is rarely encountered. When an artwork exists in urban space, the commonplace prohibitions of gallery spectatorship usually don’t apply – if you can reach it, you are perfectly free to run your hands over a paste-up, or, if you wanted to, there’s even nothing to stop you having a good sniff of a stencil.

That freedom is definitely an important part of how we look at street art and the sense of democratic spectatorship that often attaches to it. But this freedom of access comes with a downside, of course, as the artists belonging to the AMF crew from Sydney discovered, when they were arrested painting trains in London last year. The six guys have been given prison sentences ranging from 8 to 16 months (click here for more details about the case). How did they get caught? Police officers said they were alerted to the artists’ presence by hearing the rattle of spray cans and smelling aerosol paint. When it comes to art, our senses may lead us to an encounter with the sublime, but they can also be the means through which the force of law comes to be exercised.

On tagging, again: Cheyene Back’s appeal

It’s been a while since I have been able to write any entries – many apologies. I am trying to finish a book on cinema and have entered what is hopefully the last few months of that process. So I have my head down, working hard on that, and that means there’s a bit less time in the day at present.

But I did want to note what’s happened in Cheyene Back’s appeal against the sentence which was imposed upon her after she was caught tagging the outside wall of a cafe in Sydney, as previously written about in this blog. A magistrate in the Sydney Local Court had sentenced her – in a total rush of blood to the head – to a three month prison term. She appealed against this to the District Court and Judge Greg Hosking reduced her sentence to a twelve-month good behaviour bond with no conviction recorded. He commented that the previous sentence did not take into account the fact that terms of imprisoned are intended to be imposed only as a matter of last resort.

All good, yes? Well….. not quite. Judge Hosking said that it was unusual in the extreme to impose a prison sentence on a young woman with no prior record for the crime of putting graffiti on a wall – “as serious as that matter undoubtedly is”. The key issue for Judge Hosking, then, is the age and prior record of Back, rather than the issue of whether or not imprisonment is an appropriate sentence for writing a tag on a wall (and we are not talking about ‘bombing’ the city of Sydney with hundreds of tags, but rather a single tag written on a wall).

In case anyone might interpret his reduction of Back’s sentence as a wildly pro-graffiti move, Judge Hosking commented: “I’m not condoning what she did for a moment. People in Sydney are sick of graffiti, there’s no doubt about it”.

And Greg Smith, Opposition spokesperson for Justice, leapt into the media fray by adding his two cents’ worth: he thought it would be unfortunate if Judge Hosking’s reduction of the sentence meant that others were not deterred from ‘defacing property’. As The Age reported, when Mr Smith was asked if Back should be behind bars, he said: “Personally, I think she should. I think graffiti is a very serious offence. I understand that the culture hasn’t been to [imprison offenders] and we’ve got to change that culture, otherwise our city is just going to be … an eyesore.”

I know much ink has already been spilled (or many keyboards tapped on) in relation to this case, so I just want to say this. It’s amazing how graffiti can ‘press the buttons’ of – what would you call it? – ‘mainstream culture’ or ‘the dominant order’ or whatever. Clearly, the idea of a girl tagging a wall is irritating or infuriating to such a degree that both a relatively senior judge and a politician can feel able to comment that they would like to see her in prison rather than risk her (or others) tagging the walls of the city.

Two things: first of all, prisons are full. Why add to their overflowing population by sending Cheyene Back or any other graffiti writer there? Second, it is now well-documented that imprisonment can have hugely negative impacts on people’s lives – in fact, in the case of women, it would appear that imprisonment affects the mortality rate of women who have been to prison. So why do these powerful individuals – a judge, a politician – feel so comfortable saying that they would like to put this young woman in prison? What is it about tagging that drives out both reason and reasonableness?

Tagging, part 2: how a signature can lead to prison

The previous entry was about some apects of social attitudes to tagging; however, it didn’t mention one of the most important aspect of how people think about tagging – that it constitutes a crime.

Precisely which crime depends upon the jurisdiction you are in. In Victoria, it could fall under the Summary Offences Act, or if you are caught carrying something like a marker pen or a spray can, you might be prosecuted under the new Graffiti Prevention Act (see my previous post in September 2008, called ‘Clamping down’). Some jurisdictions have graffiti-specific legislation, like Victoria’s new laws, while others prosecute tagging and other graffiti activities under more generic headings.

But of course the thing is that calling tagging (or any other graffiti-related activity) a crime sets off a whole series of consequences. First of all, it categorises the activity as something that ‘society’ should be concerned about, should condemn, and should try to prevent. Next, and directly following on from that, it perm its the involvement of the police and other crimino-legal agencies and institutions, and authorises them to ‘respond’ to graffiti. Relatedly, it allows councils to create local laws which authorise the removal of graffiti (consider the fact that councils are compelled to have ‘graffiti management plans’, mainly because graffiti is considered criminal, but not ‘public urination reduction plans’, or ‘bag snatching abatement plans’). Subsequently, if an individual is discovered engaging in a graffiti-related activity, such as tagging, by these crimino-legal agencies (most likely the police), then the categorisation of tagging as ‘criminal’ means that they can be arrested, charged, and prosecuted. Once that’s done, then further consequences follow: an on-the-spot fine, perhaps, or an appearance at the Childrens or Magistrates Court.

Many people assume that when individuals get prosecuted under laws prohibiting graffiti-related activities the punishments available are not harsh. Some might assume the penalties are ‘lenient’. (After all, it’s only a property crime, right? It’s not as if we are talking about interpersonal violence.) Others might say that the available penalties are ‘not harsh enough’ (and would argue that the effects of property crimes accumulate such that their overall effects are considerable).

So perhaps it’s useful to be reminded that the punishments are not ‘lenient’ or ‘not harsh enough’. A couple of days ago, an 18-year old girl, Cheyene Back, in Sydney was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for writing on a wall in a cafe. (Check out here what the Everfresh boys had to say about this. And click here to read a thoughtful opinion piece about the case by Kurt Iveson.)

According to one news report (thanks for sending the link, Noah!), she wrote her ‘nickname’ (which I presume means her tag) on what’s described as the ‘public wall’ of the Hyde Park Cafe. I’m not sure what ‘public wall’ means – is it the outer wall, or does it mean something else? ‘Public’ wall sounds like ‘legal’ wall, but given that the action led to her being ‘caught’ with ‘a black texta at the scene’, that surely can’t be right. (Perhaps someone from Sydney who knows the Hyde Park Cafe could enlighten me as to what the ‘public wall is…)

Whatever it is, Cheyene has been convicted of the offence of ‘intentionally destroying or damaging property’, and she will go to jail as a result. And all through the chain of consequences set up by the categorisation of the act of writing one’s name on property belonging to another as ‘criminal’.

Comments (1)

Comments (1)