Archive for the ‘Art, Street Art’ Category

The textures of London

I spent a week in London recently. It’s always interesting to go back to a city after an absence of 18 months and see what’s changed. Usually it’s a matter of noticing which artworks have gone and which new ones are taking their place, but on this occasion I was struck by how much the area of Shoreditch itself had changed. Yes, there was still a lot of interesting art to see scattered through the streets, but whereas in July 2008 there were artworks around every corner, in May 2010 it would seem that the gentrification of Shoreditch has proceeded to the extent where entire streets have been so buffed that there is sometimes not even a sticker to be seen.

Fortunately there’s still a lot of work in areas such as Brick Lane, Hackney, and Bethnal Green, but you have to wonder what’s going to happen over the next 18 month as the Olympics approach. I’m guessing that there will be a huge buffing effort, and this, along with the increased surveillance (in the city that already has more cameras than any other I can think of) will inevitably have a chilling effect on the street art scene in East London. Hopefully it will simply move somewhere else in the city; it would be sad to see London lose the sense of productive possibility for street art that seems so characteristic of it.*

I don’t want to give the impression that things had already become bland – far from it. One of the striking things about this visit was seeing how lots of artists are producing works in which texture is a significant part of the visual experience: objects attached to walls, clever use of shapes and calls, a range of media, and extension of technique with paint. I know this is hardly big news, and I’m not meaning to pretend there has been any sudden shift in contemporary street art so that it’s suddenly all about texture or anything. Maybe it’s simply something that I was alert to, during this visit. Certainly some of the artworks I photographed are not necessarily ‘new’; some, in fact, have been up for a long time. But the overall effect for me was to bring out, in a very active way, the feeling of the city as existing in its textures and sensations – the material ‘things’ which make up everyday, urban life.

I’ve included a selection – see what you think.

Something simple to start with – simple, but I liked these cardboard hearts very much:

And someone is making mushroom sculptures, and placing them in high up, inaccessible spots, where they look down upon the passers-by:

More sculpture: I saw many of these amazing objects, each one different, attached high on walls, often near street corners. Great colours and shapes. Here’s a couple:

And here is one of my favourite street corners in London, and at the moment it contains a great selection of work, all placed high up, so that even the enthusiastic council cleaning crews can’t be bothered to remove them. This piece by Asbestos has been there for a couple of years now, and you can see another of the sculptures I just mentioned. There is also a little row of figures, now broken down to their torsos. You can find these on various London walls – I would love to know whose work this is.

I’m told this chair has been attached to the wall in Brick Lane for a long, long time, but now it has a satisfyingly chunky duck beside it for company:

On Rivington Street, opposite the entrance to Cargo and Black Rat Projects, there is a wall that has previously featured many paste-ups, stickers and so on. It’s pretty buffed at present, but it does have these two excellent additions.

One is a blue plaque, which reads: ‘This plaque was installed 6th May 2010’. The plaque mimics the historical marker plaques that provide information like ‘In 1856, so-and-so lived here for 2 months’, but it does so with a twist: the plaque commemorates the fact of its installation, rather than any particular event. Although it’s possible to read the plaque as having something to do with the election, the artwork is not about that as such (and it’s pleasing that the 6th of May was the day of the British general election which has subsequently acquired historical significance as the first election in Britain to result in a coalition government, but this certainly wasn’t known when the plaque was installed).

Next to the plaque, you can see a picture frame. Take a closer look:

Apparent detritus becomes art, in a work which is all about showcasing the feel and texture of things that would normally be overlooked and thrown away.

Finally, one of my main memories of visiting London this time is seeing Roa’s work in the streets. Roa is a Belgian artist whose show at Pure Evil gallery (and subsequently at Factory Fresh in Brooklyn) was a huge success, but in addition to those gallery shows he has also spent a lot of time putting work on the streets. He paints animals, usually oversized, and what’s so striking about these images is how Roa harnesses colour and spraycan technique to give an amazing sense of the texture of feathers or fur. Here’s my favourite of the ones that I saw:

And take a close look at the precision and delicacy of these ‘brushstrokes’: wonderful work.

*Thanks to Mark, from Hooked blog, for walking around Brick Lane with me….

O Superman

Sometimes travel provides an occasion to reflect upon the place you’ve left behind… While I was in New York recently, there were two different kinds of ‘home’ that I felt conscious of having left.

One was England (or Britain, I suppose). I left Britain in 1995, when I moved to Melbourne, but New York this April was full of buzz about the release of Exit Through the Gift Shop, Banksy’s movie, which I have written about here and here already, and I certainly think of Banksy as a quintessentially English (or British) artist…

New York was also full of visual reminders of Melbourne, the city that became my adopted home. As I mentioned before, one of them was Meggs’s stickers, which I saw in many places around New York.

I’ve written about Meggs before (see here), and in that entry I was discussing his work in conjunction with that of Anthony Lister, an Australian artist from Brisbane, living in New York these last several years. There are several different consonances between these two in terms of their artistic preoccupations, but in terms of simple coincidence it was amusing that while I was in New York, Anthony Lister was paying a visit to Melbourne, where he had a show at Metro Gallery.

But it’s not as though Lister was entirely gone from New York. His stickers are still very much present on the streets:

And the front of Faile’s studio was adorned with this wonderful Lister painting:

Lister also had a solo show, How to Catch a Time-Traveller, at Lyons Wier Gallery in April, running simultaneously with the Melbourne show.

Meggs and Lister are linked by more than a common nationality; there’s a strong thematic link in their fascination with the superheroes of popular culture, and comics in particular. Both create painted works as well as their own versions of action figures, miniatures and busts. Both Meggs and Lister show superheroes as figures of crisis, barely holding themselves together in the face of unknown assailants or obligations.

But in representing these highly familiar figures away from the context of comics, their methods with paint are very different, however. Meggs uses a combination of stencils and techniques from graffiti art; Lister is evolving a style that recalls Francis Bacon’s way of blurring the painted figure to create a sense both of movement and of the disintegration of the self.

In Lister’s show at Lyons Wier, its title alludes to the idea that these figures are in motion – the artist is the one with the power to stop time, to freeze the disintegrating superhero for an instant, for our scrutiny. Lister’s had a prolific career on the street for a long time, and it’s fantastic to see his painterly skills evolving. Maybe Lister’s thematic will start to broaden a little so that it is no longer simply the superhero which is subject to examination. Charlie Isoe’s current show at Lazarides in London, while containing a lot of works that seemed to me to be somewhat similar, disappointingly, to Lister’s style, showed at least what can be achieved when a wider range of objects are brought into the paintings.

What next, Mr Lister? Can’t wait to see.

Redirecting the Gaze

My first visit to New York was in 1990, a hectic day-long layover between flights. My second trip (but really the first time I began to explore the city properly) was in 1992 and a lot less frantic: five days spent, as most do, walking the city streets.

During this visit, one of my friends commented that ‘the tourist gaze is up’. What did he mean by this?

Think about moving through the streets on your way to work, or on your way to buy food for dinner. Where does your gaze direct itself? For most people, engaged in these moments of everyday passage from one space to another, the streets are something to move through while gazing either straight ahead or even downwards at the sidewalk.

Tourists, on the other hand, tend to look all around them, keen to glimpse any and all ‘attractions’ that might be nearby. They pause, they move at a slower speed, they hesitate and consult maps, often pointing their arms in the direction they are looking or in which they are about to move.

And in a city like New York, where visitors are surrounded by tall buildings, they seek to look towards the summits of those skyscrapers: hence ‘the tourist gaze is up’. And this identifying characteristic of the tourist has, by implication, a corollary: the everyday gaze is down’.

Street artists have long been aware of the downward gaze of the citizen as she moves through the commonplace activities of everyday urban life – think of Stickman’s little figures in crosswalks:

Or the stencil artists who place images and text on the sidewalk, such as these (both from San Francisco):

During my recent visit to New York, I saw two interventions in public space, neither of which might meet any strict definition of ‘street art’, but both of which manage to confound the separation between the upward tourist gaze and the downward gaze of the everyday.

The first of these is Event Horizon, a massive work by the British artist, Antony Gormley. Gormley, probably best known for his sculpture The Angel of the North in Gateshead, makes bronze casts, often of his body, and then places the resulting figures in public spaces – sometimes on a beach (as in Liverpool), sometimes in the centre of cities (as in Birmingham), and, with this work, on the tops of buildings. Instead of forging a single figure, in Event Horizon there are thirty one. Two were placed on the ground, in Madison Square Park, so that people can stand next to them, touch them, photograph them from a place of proximity:

Then, when they raise their gaze upwards to the tops of the nearby buildings, they project the heavy bronze figure from the ground upwards, onto the high perches around the park.

For the visitors, this installation fits easily into the genre of ‘cool things to see in New York’; for the locals, the statues have proved equally fascinating.

The gaze is drawn to the figures through a clever intertwining of dimensions, which gives the work tension and stops it from being yet another set of statues blandly placed in public space.

First, the figures are placed on top of buildings which reach different heights. Sometimes the figure is reasonably easy to study, such as when the building reaches to about six storeys, as in this example:

Others are positioned high above, only just visible in the vertical distance, such as this one:

The eye, then, is encouraged to travel, to meander up and down, as well as around the perimeter of the park, and to take in the variegated horizon of New York.

The second tension at work in the installation relates to the intentionality spectators project on to the figures. Why are they standing there? What are they doing? What do they represent?

The ‘figure on the roof’ is obviously one that is often depicted in film and television as someone who is about to jump – a potential suicide. And apparently the New York Police Department were briefed about the installation so that, if anyone called 911 to report someone on the rooftop, the police would be aware of the statues and their locations and would not needlessly respond to the call.

But it appears that most spectators interpreted the statues differently, as benevolent figures watching over the city and its inhabitants: guardian angels, perhaps (think of Wim Wenders’s beautiful film Wings of Desire, unforgivably remade as City of Angels with Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan).

But the tension between disaster and safety is nonetheless there in Event Horizon, and its certainly part of the phenomenon of looking that the spectator seeks to resolve that tension, one way or another. Perhaps it’s the sheer number of statues that helps the spectator decide they are figures of kindliness rather than despair, but perhaps it’s also part of the sheer optimism of New York City.

The other intervention in public space that redirects the everyday gaze is the High Line, a park that has been built around and on the tracks of a disused workers’ elevated railway, running north from Ganesvoort Street in the Meat Packing District.

You climb stairs from the street up to the park, above 30 feet up. Once there, you can walk its length, sit on the many benches and seats provided, and, above all, you can look at the city around and above and below. What’s amazing is the effect of a relatively small amount of elevation upon the way that one sees the city.

People in New York, as in most cities, are able to alter their perspective on the city by ascending to a higher level in order to look down – but this often involves ascending to considerable heights. Think of going up the Empire State Building (or in Melbourne, you might take the elevator to the top of the Eureka Tower; in San Francisco, tourists climb Coit Tower to see the undulating city spread before them).

It’s always interesting to do this – to look at a city from the ‘bird’s eye view’ that results. But looking down at the city from these heights comes at a price – loss of contact with the level of the street. Looking downwards from 80 floors up (or anything more than about 3 storeys, probably) detaches the spectator from any sense of connection with the ground: people look like ants, houses like boxes and so on. And these spaces also tend to provide fairly static viewing positions: one can walk around a viewing platform but it’s difficult to find ways whereby you can be raised up and move through the city at the same time.

One means would be an elevated railway, such as the one that was the High Line before it became a park. These certainly raise the individual up and move them around the city. But individuals are moved passively by the train, and their gaze will oftentimes remain inward within the train carriage rather than travelling out and around.

The High Line manages to transcend these limitations. When you visit the park, you move through it on your own two feet, an active participant in the space. The elevation of about 30 or so feet makes a surprisingly dramatic difference to one’s perspective, as you can see here:

Glass-fronted viewing platforms over the street allow the spectator the contemplate traffic (more interesting in fact than it sounds!) while suspended over the street:

Although some have been critical of the High Line’s redevelopment as a park (see, as an example, the discussion on Jeremiah\’s Vanishing New York), its impact on the citizen’s experience of the city is undeniable: lifting people up while allowing them to move or rest at will reconfigures them in public space and, as with Gormley’s Event Horizon, it promotes a new kind of relation, albeit temporarily, with the city that lies above, around and below.

Art, Value and Banksy’s Rats in Melbourne – visit Hyperallergic

If you have been following the recent street art debacle in which Melbourne City Council ‘accidentally’ buffed one of Banksy’s rats in Hosier Lane in Melbourne, you might be interested in reading my account of this event, over on the excellent site Hyperallergic.

Lapse of time II

As mentioned in the previous post, when I visited New York in 2005, I spent a lot of time walking around the Lower East Side, the East Village, and SoHo, and there was, as you can see in the photos, a vibrant street art culture taking place there. Arriving here two weeks ago, I knew that the scene had shifted, that gentrification had caused many artists to move out of Manhattan and into areas like Williamsburg in Brooklyn, but on my first day here I took a walk around the areas that had been so filled with artworks five years ago.

My memories of that previous visits are so clear (and the photographs I took are much treasured), so it felt quite disorienting to discover how much those areas of the city have changed. I know that cities don’t stay the same, of course, that they are constantly engaged in a process of transformation and redefinition. This process is often imperceptible when you live in the city, but when you make occasional visits separated by a gap of several years, sometimes the differences are striking.

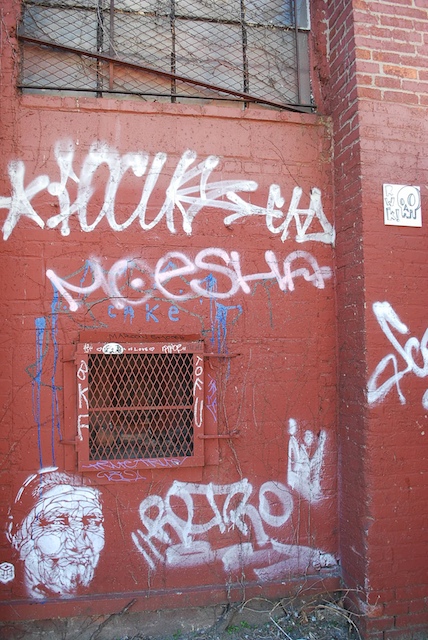

And so in 2010 I discovered that the Orchard Street Gallery was no more (but I was relieved to find out that Ali Ha and Ad DeVille have opened Factory Fresh in Bushwick instead). I couldn’t see many stencils or paste-ups. There were loads of tags, and a huge amount of sticker action, especially on phone booths, mail boxes and doorways. The desire to exploit the adhesive nature of certain surfaces leads to some pleasing accidental patterns, as you can see below:

I also came across a nice dripped portrait:

New to me also was this massive piece by WK Interact, which you can see up on the rooftop, below the billboard for Marina Abramovic’s show at MoMA:

There were also some works by artists who were not on the scene 5 years ago, such as Elbow-Toe:

And, late on my first day in New York, while I was still feeling as though I was somewhat in between two cities, I came across an image from home.

In the midst of other stickers and tags on this doorway, there’s a sticker which says ‘Damn You Meggs’ – Meggs is a member of the Everfresh collective in Melbourne (and I’ve written here previously about his work in connection with that of D*face and Anthony Lister).

Seeing this sticker reminded me how important travel is in the world of street art – that artists can circulate around different cities, bringing their images from one to another, and that the result is a strong community, so that you can feel at home, even when you are 12,000 miles away.

Banksy at the movies: Part II (Banksy’s hands)

Since the previous post, about expectations of what Exit Through the Gift Shop is about, turned out to be a long one, I thought I’d write a separate one dealing with what it’s not about.

So let’s go back to the second response that a lot of people seemed to have after seeing the movie – a feeling of surprise that it’s not ‘about’ Banksy, or at least not as much as they had expected.

It’s worth looking at this closely. Is the film ‘about’ Banksy? Well, the film is made by him, and thus it provides us with a text which tells us something about the artists and his concerns, just as his artworks, books and exhibitions do.

And then again, Banksy is in the movie: we see him in his studio; we see him stencilling; we see him with his crew of helpers creating the famous ‘vandalized telephone box’ in London (which goes on to sell for an extraordinary sum at auction); we see him installing a blow-up doll, hooded, shackled, and wearing an orange jumpsuit, at Disneyland, in a direct juxtaposition of American mass entertainment culture with the torture of detainees at Guantanamo. (All of these occurrences are filmed by Guetta.)

But of course, while all of these events are taking place, Banksy still withholds himself from any kind of identifying gaze – he wears the hood of his sweatshirt pulled over his head, his face is blanked by pixillation, his voice distorted (and his assistants’ identities are similarly masked).

So Banksy’s certainly in the movie, but he’s simultaneously on display and hidden from our view. But what we do see in plain sight are his stencils and his hands: as Banksy himself states in the film, ‘I told Thierry he could film my hands but only from behind’.

As he says these words in voice-over, the film shows us Banksy at work, cutting stencils (for one of his signature rats, to be put up on a wall in LA). And for me, that was one of the highlights of the film – watching those hands, whether at work on the stencil or gesturing along with the words spoken by Banksy’s distorted voice.

They’re slender hands, with long fingers. They’re the hands of an artist. What does the face matter, or the voice? Watch the film – and watch out for the scene of Banksy cutting stencils, with speed, and with great skill. That moment might not be central to the film, but it’s certainly what street art is all about.

Banksy at the Movies: Part I

I’m in New York City right now, and last night I attended a preview screening of Banksy’s film, Exit Through the Gift Shop. The film is being released in a number of US cities from April 16th and if you click here you can find a list of release dates, cities and theaters. (If you’re reading this in Britain, the film’s been out for a few weeks; if you’re reading this in Australia, be patient a little longer because the film will be released there in early June.)

Given the intense interest in Banksy as an artist and in the mystery of his identity, it’s inevitable that this film will attract a lot of attention. What’s as interesting as the movie itself is the range of responses that people are having to the film. Among those who’ve seen it so far, people speak positively of the film (as they should, since it’s a highly enjoyable documentary), but they also seem, first of all, surprised that it is more about Mr Brainwash (aka MBW aka Thierry Guetta) than it is about Banksy; and, second, disappointed that, because the film is more about Mr Brainwash, Banksy doesn’t reveal much of himself in the movie.

Let’s start with the first of those reactions, that the film’s not ‘about’ Banksy, which certainly raises the question of what the film is about. Well, the film operates on many different levels, and one of its main ones is the story of how street art took off, from being something with an intense local significance which was shared through the networks of the global street art community for the enjoyment of those who practice or appreciate street art, to became an entrenched part of the mainstream art world, whereby paintings (and artists) are commodified for profit.

To tell that story, the film focuses on Thierry Guetta’s transformation from amateur film-maker into artworld succes du jour, as a means of demonstrating both the possibilities open to anyone with the will to put up art and the (slightly frightening) logical consequences of those possibilities (for example, having people queueing for hours to get into your art show, simply because they’ve been told by the media that your art is important).

The film treads a clever and careful line between condoning and critiquing the commercialization of street art, as its embodied in Guetta’s transformation: it really is left up to the viewer to work out where you stand on the issue. In some ways, the film seems to be criticizing the people who have bought Mr Brainwash’s work for vast sums of money and who have contributed to his art world stardom, but, then again, isn’t this the same art world that has made stars of Shepard Fairey and Banksy and Blek le Rat? If we want to critique the art world, it must be a critique that can specify why Mr Brainwash’s stardom is problematic when that of the others is not.

So: how do we think through that problem? Is it because Mr Brainwash doesn’t make all of his art himself? Neither does Shepard Fairey nowadays, nor Banksy (both of whom have assistants – and we see some of Banksy’s assistants at work in the film), and neither does Jeff Koons, for that matter. Is it because Mr Brainwash’s work is derivative (his work repeats many of the devices used by Andy Warhol, Banksy, Fairey, Nick Walker, Blek…)? Well, that might be a better founded criticism, but it still requires us to think through its implications: each of those artists borrow from other artists and art movements, re-presenting certain tropes in order to create a new art idiom. Perhaps Mr Brainwash’s endless borrowing (what some would even call plagiarism) from the borrowers lacks aesthetic merit because it does nothing new – no new idiom emerges from his pillaging of pop culture and street art.

At any rate, I think these issues form the heart of what the film is about – and I’d back this up by referring you to the movie’s title. By calling his film ‘Exit Through the Gift Shop‘, Banksy is both having a sly dig at museum culture, which often cynically seeks to extract more money from visitors after they have viewed an exhibit, but he is also pointing out to us the direction that street art may be heading in, now that its commercialization is so advanced – the only ‘exit’ is to find a way through the endless consumption offered to us as a poor substitute for the art itself.

Comments (5)

Comments (5)